Dental Advice

This information page was developed after feedback identified a lack of online information to inform patients when they are diagnosed with head and neck cancer. The information leaflet was developed through collaboration between Oracle Head and Neck Cancer UK, a specialist in Restorative Dentistry, and our patient and carers group, Oracle Voices.

Prehabilitation

Head and neck cancer treatment can influence the health of your mouth by altering the shape/structures in your mouth, reducing the amount that your mouth can open, causing oral dryness, increasing your chances of developing dental decay, and increasing the chances of developing tooth pain and sensitivity. Minimising these negative effects should form a key part of your treatment planning process. This can involve preparing your mouth before the start of cancer treatment. Medically, this is called prehabilitation. The aim of this is to ensure that your mouth is as healthy as possible before the start of cancer treatment. Prehabilitation could involve removal of infection, improving your gum health, mouth opening exercises, and treatment of decayed teeth. The process may also involve guiding you on your brushing technique. Prehabilitation can reduce the pain during radiotherapy, and support healing after surgery. It is important to note that you may not require oral prehabilitation prior to cancer treatments if your oral health is already good.

A pre-treatment assessment appointment with a specialist in restorative dentistry is important if the cancer or its treatment could affect your oral health.

Dental extractions before cancer treatment

The restorative dentist may recommend removal of teeth prior to cancer treatment. This is to remove infected/decayed teeth and reduce the chance of dental complications in the future. Keeping healthy teeth and supporting your oral health is the priority, however in some cases many or all your teeth may require removal, especially if they are very decayed or wobbly. Current recommendations advise 2-3 weeks of gum healing between dental extractions and the start of radiotherapy.

Radiotherapy affects the ability of your jaw bone to heal. Keeping decayed teeth or delaying dental extractions increases your chance of developing a non-healing or infected jaw bone (osteoradionecrosis). Osteoradionecrosis develops in 7-10% of people who have extractions following radiotherapy. This is a condition which is difficult to treat, and can result in significant pain, infection, and limitation to your mouth opening.

Dental rehabilitation

Some patients will experience a significant deterioration in their oral health following cancer treatment. This can be a direct consequence of cancer treatments, or a result of dental decay and gum disease occurring after cancer treatment.

Long-term prevention of this is particularly important and typically involves a combination of:

- Carefully managing how frequently you consume sugary foods and drinks

- Effective and frequent tooth brushing with high fluoride toothpaste

- The use of salivary mineral replacements such as Tooth Mousse®

- 3-monthly dental examinations to identify and treat any dental disease early

If surgery is likely to affect your oral health, then a specialist in restorative dentistry will explore the benefits of dental implants. Dental implants may not always be possible or appropriate. Where this is the case, a Specialist in Restorative Dentistry will discuss alternative tooth replacement options such as dentures/obturators and bridges with you. An obturator is a type of denture that is used to block a hole that may be left between the roof of your mouth and your sinus or nose. This may be required if you require surgery to your top jaw. The obturator stops food and liquid from moving between your mouth and your nose, and can also be used to support your cheek if part of your cheek bone (zygoma) has been removed.

All tooth replacement options require very good attention to oral hygiene. It is important to consider your ability to achieve this when considering which option is right for you. It is also important to note that you may not require tooth replacement options if you are missing no teeth, or only a small number of back teeth. Many people find that they can eat, speak, and smile without any difficulty if this is the case.

Dentures

Dentures are a useful way to replace teeth, particularly if you are missing many teeth. They can also be useful as a temporary replacement for your missing teeth. They often have a good appearance as they can replace both teeth and gum, and can in some cases provide support to your face if surgery has affected this.

Dentures are a removable replacement for tooth. This means that you typically remove dentures to clean them, and keep them out overnight or for a few hours each day. This helps to maintain the health of your gum. Dentures rely on health gum to help keep them stable and comfortable. This also means that if your mouth is sore, dry, or unhealthy then denture wearing may be uncomfortable or impossible. The extent and type of surgery you have had, and the area of radiotherapy you have had will also affect this.

Bridges

Bridges are a fixed replacement option for missing teeth. Whilst this is often desirable, bridges can only replace tooth and not gum. They can also only replace one-two teeth. Your teeth must also be healthy enough to support prosthetic/bridge teeth. The replacement of teeth using a bridge is therefore more common when one or two teeth are missing.

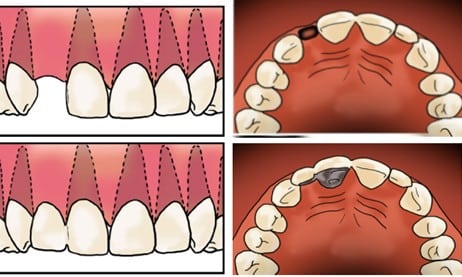

Examples of a bridge used to replace a missing tooth is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Top left and right shows a person missing on of their front teeth, bottom left and right show replacement of this missing tooth with a bridge which uses another tooth for support. This type of bridge is referred to as a resin retained bridge.

Dental implants

Dental implants are titanium screws that are surgically placed by a dentist in the jaw or cheek bone and are used as anchors to replace missing teeth with bridges or dentures. They can be used to provide a fixed or removable way of replacing missing teeth.

Dental implants have a 90-97% success rate in people who have had head and neck cancer treatment, but they are not always possible or the best option. Whether or not this is the case will depend on circumstances unique to you. Dental implants require careful planning to ensure that there is enough bone, and healthy gum to replace missing teeth. If dental implants are an option to replace any of your missing teeth, then a restorative specialist will perform this assessment for you.

In some instances, dental implants will be placed during your cancer surgery. These are buried in jaw bone for several months to enable your bone to heal around them. In rare instances, you may receive a temporary replacement for your teeth within 1-3 months of surgery. More commonly this will happen approximately 1 year after your surgery, especially if you have radiotherapy.

An alternative option may involve dental implant placement after cancer treatment. This option is avoided where possible if you are planned for radiotherapy: this is because of the risk for osteoradionecrosis. If you have had radiotherapy and would like to know more about dental implants, then your restorative dentist will work with your oncologist to discuss the risk of osteoradionecrosis with you: dental implant placement may not be possible if this risk is too high. If dental implants are possible then the process of replacing your missing teeth with dental implants may require 12-18 months of dental treatment. The process typically involves:

Figure 2 showing tooth replacement with dentures and implants (1), and with crowns/bridges and implants (2)

- Implant/prosthetic planning with a CT scan of the jaw

- Implant placement (possibly with bone grafting)

- In some cases bone grafting may need to be performed four-nine months before implant placement

- Three months of bone healing after implant placement is needed to ensure predictable healing of jaw bone up to the implants.

- Implant restoration (making and fitting a bridge or denture to fit onto the implants)

- This process required 6-7 appointments spaced two-three weeks apart

Figure 2 shows examples of tooth replacement with implants.

Tooth replacement options are personal to you. Your cancer team, including your restorative dentist, will discuss the risks and benefits of each option as well as what the potential treatment will involve. The aim of this process is to guide you through your oral rehabilitation decision making process. It is important to note that smoking and oral hygiene both affect the success of tooth replacement options. You must quit smoking and ensure that you have good oral hygiene before implant treatment can be provided.

Osteoradionecrosis (ORN)

Osteoradionecrosis is a complication of radiotherapy. This typically develops in the months or years following completion of radiotherapy. It is the necrosis (death) of jaw bone due to the body’s impaired ability to heal and maintain tissues after irradiation. The condition affects 7-10% of people who have had radiotherapy and is more likely to occur if you:

- Have had dental extractions after radiotherapy

- Needed a large number of dental extractions before radiotherapy

- Smoked, especially during or after radiotherapy

- Have poor oral hygiene during or after radiotherapy

- Receive a high radiotherapy dose to the lower jaw bone

Prevention

Prevention is the best management of osteoradionecrosis. A restorative dentistry assessment involving “prehabilitation” and dental extractions (if required) is crucial to reducing the risk for osteoradionecrosis. Please see the oral rehabilitation section for more information. Long-term recall (dental check-ups) is also important to maintaining your oral health and, therefore, preventing dental infections and the need for dental extractions, which may increase the chances of osteoradionecrosis.

If dental extractions are required, it is important to re-evaluate the dose of radiotherapy given to the patient to determine the risk of osteoradionecrosis. Dental extractions may be undertaken in stages and combined with other treatments such as antibiotics, mouthwashes, and certain medications. There is no clear evidence on the best way to prevent osteoradionecrosis if dental extractions are required.

Treatment

Most cases of radiotherapy affect the lower jaw (approximately 90% of all cases), and can start with jaw pain or aching. In some cases, there may be no symptoms in the early stages of necrosis. Osteoradionecrosis is caused by a combination of changes to the strength of your jaw bone (which becomes more scarred/fibrous) and a reduced blood supply to the jaw bone. It is difficult to treat osteoradionecrosis, and there is not an effective cure for this.

In some cases, when the area of necrosis is very small, it may heal over time. Your doctor may prescribe antibiotics or a mouthwash to treat an infection and help you clean the area effectively.

It is common for loose fragments of bone to either be removed by a healthcare professional, or for these to come out by themselves. In some cases, the maxillofacial surgeon will clean the area surgically and remove larger areas of bone.

In addition, certain medications may help the tissues heal after osteoradionecrosis. There is no clear evidence whether any of these help; however, there is ongoing research in this area. One clinical trial (the RAPTOR trial) is investigating the use of three different medications in combination to treat osteoradionecrosis.

Osteoradionecrosis can progress, often at a slow rate. This can lead to infection coming out from the jaw bone or face. If left untreated, the condition can be life-threatening. In rare cases, the maxillofacial surgery team may remove a large portion of jaw bone in a similar manner to a cancer resection. They may then leave the remaining jaw bone to heal, using a plate to join separated fragments. Alternatively, the area may be reconstructed with a free flap, typically from your leg, hip, or shoulder. This surgery is difficult for the surgeon for the reasons outlined above: your tissues will be altered by radiotherapy and will, therefore, be more scarred and have less of a blood supply. Note – “Free flap surgery” involves the transfer of a patient’s own tissue from a donor site to a recipient site, which is typically the site of a defect. The donor site usually has a distant location with respect to the recipient site.