The late Sir John Hervey-Bathurst and salivary cancer

Sir John’s son and Co-founder of the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation (HNCF) Sir Frederick Hervey-Bathurst explains how his father’s battle with the disease inspired him to increase awareness and iunvestments in research.

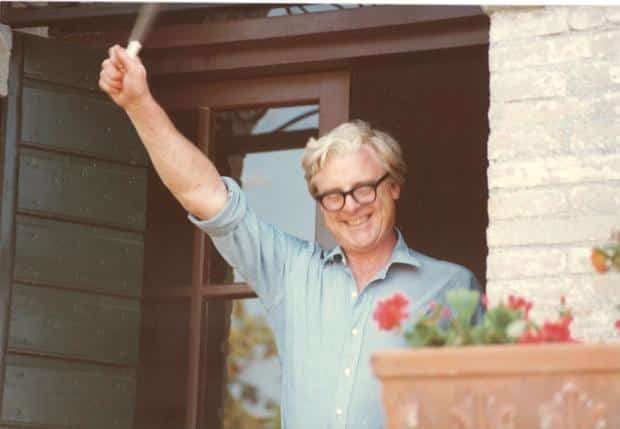

“My father was exceptionally hard-working, enjoying a successful career in the City, but always put his family first and at weekends delighted in caring for and restoring our beautiful family home in Hampshire.

Treatment for salivary gland cancer

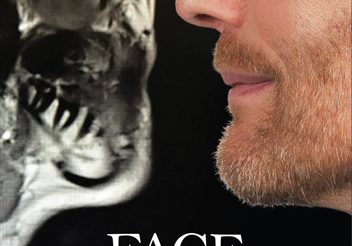

It was during a routine visit to the dentist that a tumour was spotted inside my father’s mouth. He was immediately referred to hospital and, shortly afterwards, Professor Mark McGurk operated to remove a large cancerous tumour.

The operation was gruelling and lasted 13 hours. Part of my father’s tongue, the top of his mouth and a section of his jaw was removed. He was disfigured but alive, and a new chapter in his life had begun.

My father survived a further 19 years and never once in that time did he ever complain or show anything other than a stoic approach to life. He might easily have become a recluse, confining himself to his home, but instead decided to focus on living life with his usual gusto and determination.

After the operation, our family formed a wonderful friendship with Mark McGurk and his family. Two decades later, following my father’s death, Mark mentioned to me the huge advances made in surgical procedures. In particular, it was now possible to minimise the physical impact of facial surgery. However, although these advances were proven, they were yet to be adopted by other surgeons. It was, and remains, vital that more surgeons and oncologists are trained in these advances so that they can deliver these new life-changing treatments to as many patients as possible.

Long term side effects from salivary gland treatment

My father treasured every moment of his life after his operation but suffered for nearly two decades in ways which would have crushed many individuals. Verbal communication was almost impossible, he was facially disfigured and had to take in most of his nutrition through a stomach peg. Wonderfully – almost miraculously – for so many people this is no longer necessary. For this reason, I was delighted to accept the role of Chairman in the certain knowledge that the HNCF, with Mark’s leadership, can and will improve the outcome for others who suffer this terrible disease. My enthusiasm is driven by a passion borne of what I have witnessed and the knowledge that we can, and will, improve the lives of countless others”.

Sir Frederick’s sister, Sophie Colthurst, added her personal take on their father’s story. “My parents had eight grandchildren and I firmly believe it was this strong family network of support that made such a difference, especially during my father’s later years. How lucky we are to have such a large family and how fortunate that his grandchildren got to spend lots of time with him. For this, I am so grateful.

Following surgery, initially he could not speak and he found this very frustrating. Visitors would come to the hospital and try to engage him in conversation – he would find this exasperating though, as he could not talk or ask questions.

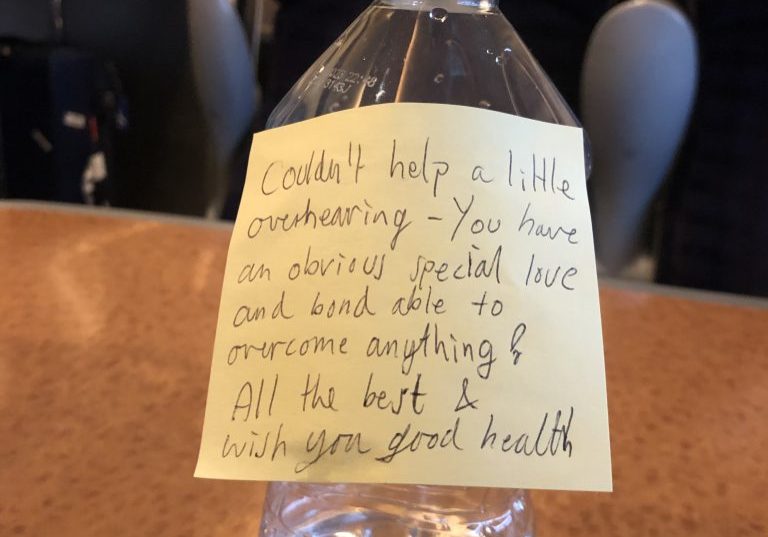

His grandchildren just accepted it. They all handled things very well and did not react to his scarring – that gave him a huge amount of confidence. When they first visited him in hospital after the operation then hugged any part of him they could – even a leg sticking out from under the blanket. This physical contact reassured him and he knew he was loved.

Reflections on coping with side effects

Many years later he told me that the main thing which got him through his post-operative recovery period was my mother’s physical presence. She would sit by his bedside and say nothing. He knew that she was there and he could sleep, knowing that she would be there when he woke and that she had no demands from him, no questions and no conversations to have. He referred to her ‘medicine’ as calm, serene and reassuring. My mother would sit beside him and sketch or read to him – giving him contentment.

As time passed my father became very reliant on writing. He always carried a pad and pen with him and would frequently write us notes. He took to writing his grandchildren letters, packed with his thoughts, advice and suggestions of things to do, places to go and books to read.

Very quickly after his recovery, my father decided to do what he could do and not to focus on what he couldn’t. He became very proficient on his computer and taught himself to do lots of things with it. He was a highly intelligent man and his lust for knowledge never left him – even during his illness. He loved to understand exactly how things worked, with an impeccable eye for detail and a curiosity for the ‘nuts and bolts’ behind everything.

Our family was exceptionally lucky as we enjoyed another two decades together. I hope our story will inspire other people to check their mouths regularly and to seek advice if they spot anything.”

Listen to Sir Frederick on a Get Mouthy podcast on Spotify – https://open.spotify.com/episode/5mR5lI6kU6AspGQqN4WKlN?si=b34f99e4f4954a85

Patient Stories

Suzie Cooke – a lesson in not taking ‘no’ for an answer

Nigel Lloyd-Jones – being told “you have cancer” is life changing

Belinda Gilfoyle – a slow recovery and learning to stay positive

Salivary Ductal Adenocarcinoma news “hit me like a train”